See our paper here (open access).

Male birds-of-paradise are justly world famous for their wildly extravagant feather ornaments, complex calls, and shape-shifting dance moves—all evolved to attract a mate. Our new research published in the open-access journal PLOS Biology suggests for the first time that female preferences drive the evolution of physical and behavioral trait combinations that may also be tied to where the male does his courting: on the ground or up in the trees. There are 40 known species of birds-of-paradise, most found in New Guinea and northern Australia.

Our study’s lead author Russell Ligon, a postdoctoral researcher at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, suggests females are evaluating not only how great the male looks but, simultaneously, how well he sings and dances. Female preferences for certain combinations of traits result in what the researchers call a “courtship phenotype”—bundled traits determined by both genetics and environment.

We examined 961 video clips and 176 audio clips in the Cornell Lab’s Macaulay Library archive as well as 393 museum specimens from the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, concluding that certain behaviors and traits are correlated:

As the number of colors on a male increases so do the number of different sounds he makes.

The most elaborate dancers also have a large repertoire of sounds.

Males that display in a group (called a lek) have more colors to stand out better visually amid the competition.

Because female birds-of-paradise judge male quality based on a combination of characteristics, the study suggests that males may be able to evolve new features while still maintaining their overall attractiveness to females—there’s room to “experiment” in this unique ecological niche where there are few predators to quash exuberant courtship displays.

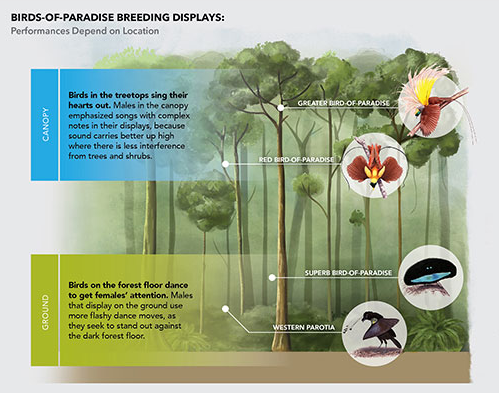

The researchers found that where a bird-of-paradise puts on his courtship display also makes a difference.

“Species that display on the ground have more dance moves than those displaying in the treetops or the forest understory,” explains Edwin Scholes, one of our study’s co-authors and leader of the Cornell Lab’s Birds-of-Paradise Project. On the dark forest floor, males may need to up their game to get female attention.”

Above the canopy, where there is less interference from trees and shrubs, males sang more complex notes, where they are more likely to be heard. But their dances were less elaborate—perhaps a nod to the risks of cutting footloose on a wobbly branch.

This study was conducted by scientists at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, the Department of Neurobiology and Behavior at Cornell University, the Centre for Ecology and Conservation, College of Life and Environmental Science at the University of Exeter in the U.K., and the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard University.

The work was funded by a grant from the National Science Foundation.

Reference:

Ligon, R. A., C. D. Diaz, J. L. Morano, J. Troscianko, M. Stevens, A. Moskeland, T. G. Laman, and E. Scholes III. 2018. Evolution of correlated complexity in the radically different courtship signals of birds-of-paradise. PLOS Biology.

Be First to Comment